Building an Altar

A portion of Chapter 5 of Building Benedict-Benedict Builds

If you work the words into your life, you are like a smart carpenter who dug deep and laid the foundation of his house on bedrock. When the river burst its banks and crashed against the house, nothing could shake it; it was built to last (Luke 6:48 MSG).

Building an Altar

Ergo nihil operi Dei Praeponatur. RB 1980, 43:3

Therefore nothing should be put ahead of the Work of God (Kardong. Benedict’s Rule, 354).

He [Abram] moved on from there to the hill country east of Bethel and pitched his tent between Bethel to the west and Ai to the east. He built an altar there and prayed to God (Gen 12:8 MSG).

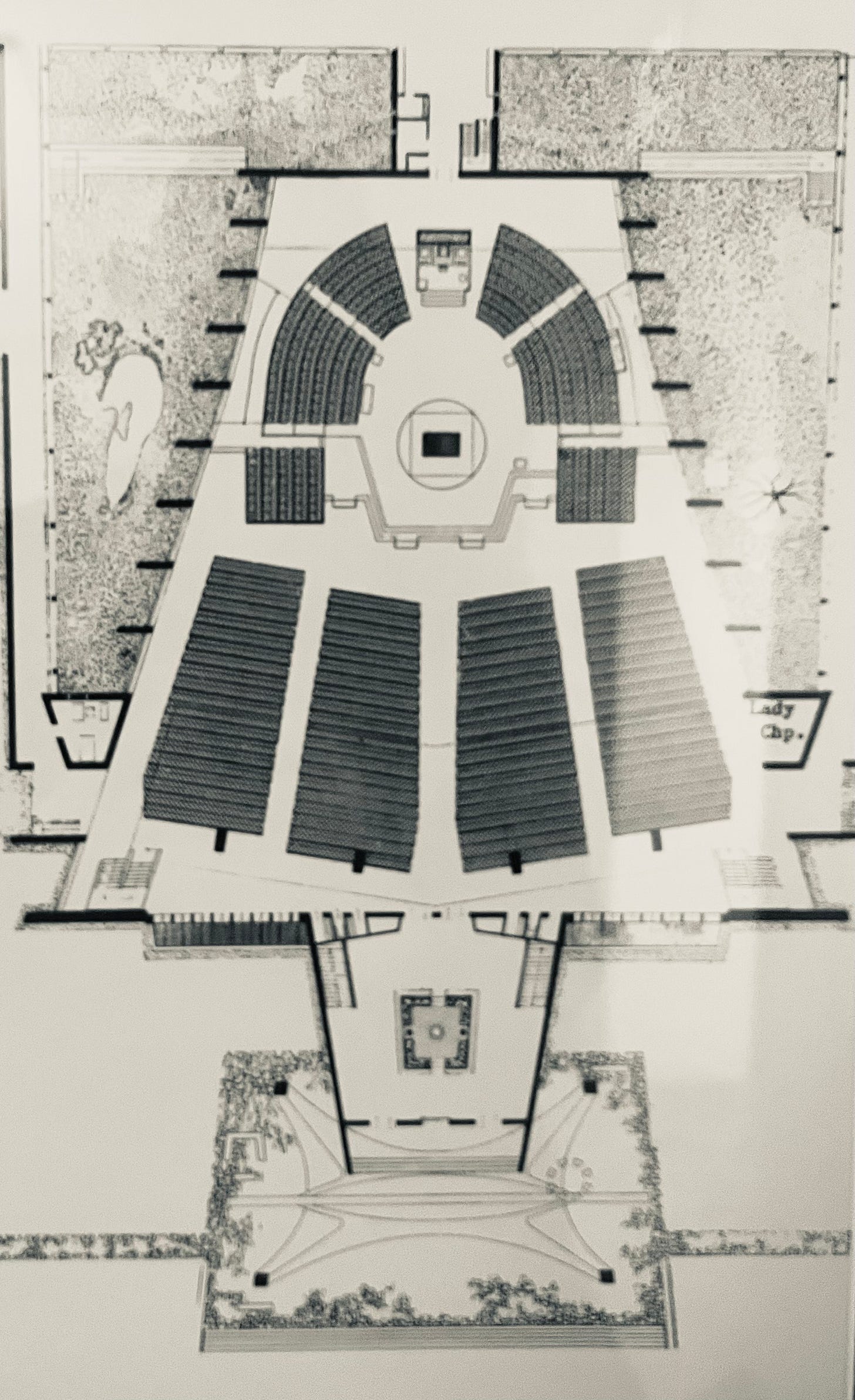

Incense rises and everyone bows as we sing Mary’s subversive canticle at Evening Prayer on Sunday at St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota. The new week is beginning, and the proud need to be scattered in the thoughts of their hearts, the mighty brought down from their thrones, that our souls might magnify the Lord, and that he might raise up the lowly. The altar is censed then the congregation—the place of prayer and the people of prayer. This was my first week in residence adjacent to the Abbey, at the Collegeville Institute, but it isn’t my first time to St. John’s. The first time I came by Greyhound bus in the Summer of 1992. Departing from my home in Seattle two days earlier, we stopped at nearly every town and were finally nearing Minneapolis, my destination. I had seen the worst street in every town. That is where they put Greyhound stations. As eager as I was to reach my waiting friends when that driver exited I-94 and ascended Abbey Road, the sight of the chapel made me want to disembark prematurely. Eyes fixed on the largest narthex I’d ever seen, I didn’t notice the surrounding college buildings, stadium, and students. An imposing concrete structure designed by Bauhaus architect, Marcel Breuer, the entrance, by a wall of glass reminiscent of an enormous beehive, feels more permeable, not brutal. Protective, but not defensive. The front door was not a function but a feature. This was a stable shelter, and I, a wandering passenger on a Greyhound bus full of wanderers. I didn’t stay that day, but I wanted to. And, if I had, I would have found that those doors led to aisles, extensions of walkways, which were themselves extensions of roadways that all led to one place—the altar.

The altar is the place of encounter, the sacramental and the sacrificial in perichoretic conversation. God calls. Mortals come. God speaks. Mortals respond. Humans offer their beggarly bread and wine. Jesus, his own flesh and blood. The priestly people intercede on behalf of the world they inhabit, and God blesses those same people with a benediction to be a benediction for the sake of the world. The absolved become absolvers. The reconciled, reconcilers. The blessed, become blessings. The gathered people need a place to gather and to encounter God, together. The altar is that place.

The whole God-made world was a garden-temple, an altar of encounter for our first parents. They encountered God everywhere, except in the little cramped world off in the corner that they made for themselves. There, they set up a quickly handmade altar to their own agenda, a place of devotion to themselves, a place of faith in the serpent’s voice. This would commence billions of altar-builders constructing places of sacrifice in search of satisfaction. The Areopagus in Athens, with its panoply of altars, reflects this altar-filled world of gods known and unknown.

As we establish community, we don’t begin from a world empty of altars, but full of them. Our lives are the same. Some of these altars have traditional gods associated with them. Most of them, though, seemingly innocuous, demand a pinch of incense and a credo, “Youth sports is Lord,” or “Work is Lord,” or, “Physical fitness is Lord.” They strike their own covenant. In exchange for oblations of sleeplessness, over-production, long hours, doting attention, and other sacrifices, these altar-gods offer identity, purpose, salvation, and satisfaction. But one day, much earlier for me than others, one retires from youth sports. Work comes to an end. Bodies wrinkle and sag.

Every altar shares this in common: the demand that nothing is preferred over the worship that takes place there. Altars expect primacy and require the utmost, the highest commitment. Managing all these altars is challenging, exhausting, and impossible.

It is no wonder that in a world of all these altar-gods, patriarch and prophet, king and priest would nearly all build or restore the altar to the living God. One could choose many examples on which to reflect. The most vexing and relieving, might be Father Abraham’s altar on a mountain, where he was going to offer Isaac as a burnt offering to God. Climbing up mountains was commonplace for bloody sacrifices to be made to the gods. But God would turn all this upside down. The oblation wouldn’t aim heavenward, but would be earthbound.

Then Abraham reached out his hand and took the knife to kill his son. But the angel of the Lord called to him from heaven and said, “Abraham, Abraham!” And he said, “Here I am.” He said, “Do not lay your hand on the boy or do anything to him, for now I know that you fear God, since you have not withheld your son, your only son, from me.” And Abraham looked up and saw a ram, caught in a thicket by its horns. Abraham went and took the ram and offered it up as a burnt offering instead of his son. So Abraham called that place, “The Lord will provide,” as it is said to this day, “On the mount of the Lord it shall be provided” (Gen 22:10-14).

This would be God’s altar-way: providing fire at Mount Carmel, making atonement in tabernacle, Temple Mount, and Mount Calvary. “On the mount of the Lord it shall be provided.” This God doesn’t demand a pound of flesh and blood from you for the forgiveness of sins, but on his altar, gives and sheds “for you, for the forgiveness of sins.” All the other altars demand, this one delivers.

Benedict would, as patriarch and prophet before him, and as a matter of priority, address the pagan altars and then build one for the living God.

If you would like to read more of Building Benedict—Benedict Builds: Benedictine Wisdom in Building Leaders who Build Communities in a Seismic Age, please reach out. I’d love to share a link.